“I’m not laughing at you, I’m laughing with you.”

“But I’m not laughing.”

One of the most feel-bad comedies ever made, Happiness is firmly on the list of those must-see films you might only ever watch once. Todd Solondz’s follow up to Welcome To The Dollhouse has a similar off-beat, dark sense of humour running through it, but here Solondz juxtaposes moments of absurd humor with horrifying realities, creating a work that is both disturbing and darkly comic. Despite its relentless bleakness, the film’s empathy for its flawed, often repellent characters elevates it from shock value to something more profound.

A pitch perfect ensemble cast plays an assortment of lonely, untethered characters, all of whom are seeking love, connection and happiness in their own, often twisted way. Allen (Philip Seymour Hoffman) feels compelled to make dirty phone calls instead of actually talking to his neighbour, author (Lara Flynn Boyle) who herself is seeking fulfillment in a series of one night stands. Her sisters are the ironically named Joy (Jane Adams) an aspiring musician who spends the film getting treated terribly by everyone she meets, and Trish (Cynthia Stevenson) the gossiping, superior wife of psychiatrist Bill (Dylan Baker), who has his own dark secret. Rounding out the family are the sisters’ mother and father (Ben Gazzara and Louise Lasser) who are having a not so amicable separation – though categorically *not* a divorce.

Calling Happiness bleak is putting it mildly. It’s one of the few films I’ve seen that made me want to go and have a shower when it was over. What prevents the film from being a relentless slog, or a pure exercise in bleakness, is the tenderness with which Solondz treats all his characters. They are all depicted as real people desperately reaching out for love, for a chance to connect with someone, anyone. Solondz clearly cares a great deal about his characters, all of whom are played sympathetically, which is really saying something when one of those characters is an active paedophile.

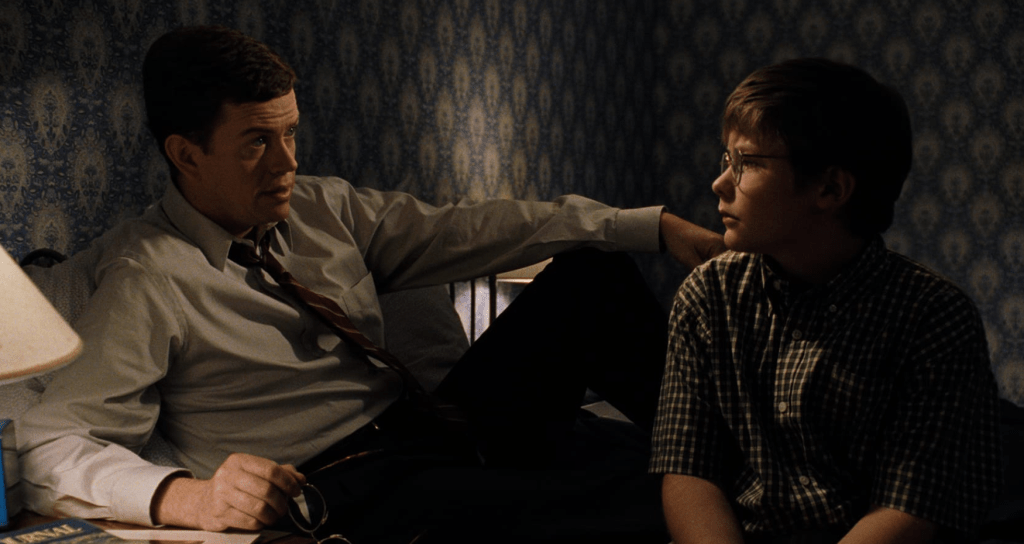

The genius of the film lies in the characterisation. Dylan Baker is a genuinely sympathetic actor, and he makes his character empathetic and likeable in his early scenes. Baker is so great in the role, but what is remarkable about his performance today is just how un-showy it is. He never hams it up or makes Bill an over the top villain. He plays him just like a normal, unassuming man, which makes him even more disturbing. He ends the film as an unrepentant monster, and despite the irreverent tone elsewhere, the horror of his character is played completely straight.

Even when his monstrous actions put him well beyond the realms of sympathetic, there is enough of that residual likeability left to make you gasp once it all comes crashing down. It’s a very Hitchcockian technique – in Psycho, Shadow Of A Doubt, Strangers On A Train and Frenzy, he would force you to identify with the villain by putting them in a situation where you inadvertently end up rooting for them. When Bill slips up in the police interrogation there’s an almost visceral “Oh s***” reaction from the audience.

Solondz obviously never attempts to justify Bill’s urges, and yet Baker’s performance puts you completely in his shoes, to the extent that when he gets that phone call late in the film, you get that horrible knot in your stomach along with him.

The final scene between Bill and his son Billy (Rufus Read) is simultaneously horrifying and tender. There’s an uncomfortable contrast drawn between the paedophile who has an open, honest relationship with his sexually frustrated son, and the father of the victim, who wants to hire a prostitute to turn his “gay” son straight. Billy’s relationship with his father, messed up as it is, is shown throughout as a loving, honest one, and the boy’s final jubilant line, “I came!” is funny, almost triumphant, and at the same time tragic, because the people he is talking to look at him like he’s a little freak. He’s lost the only person in his life who would react without judgment.

For all the bleakness and domestic horror though, Happiness also contains a handful of some of the funniest scenes in cinema. The extended intro with Jon Lovitz (in his only scene in the film), just about the most bitter break-up scene ever filmed (“I’m champagne and *you’re* s***!) or Allen’s initial therapy session where he monologues about being boring in a boring monotone. It also features heartfelt, tenderly observed performances from a cast who perfectly understand the assignment. Jane Adams is particularly great as the perennially hapless Joy, who endures indignity after indignity in her search for love, while Cynthia Stevenson gives maybe the films most understated performance as her insufferable elder sister, who constantly deploys micro-aggressions at her siblings with condescending, patronizing comments.

Solondz continually undercuts superficially romantic or sentimental scenes, and there’s a definite cruel streak in the way Joy is continually mistreated, but I still wouldn’t call Happiness a cynical film. For every bleak moment there’s the potential for something new. Even the way Jared Harris’ Russian cheater says “Stupid American” is accompanied by an almost wistful music cue. The film’s empathy for its flawed, often repellent characters elevates it from mere shock value to something more profound.

Solondz has said before that Happiness couldn’t be made today, and it’s hard to disagree. While modern cinema might address similarly taboo topics, it’s unlikely anyone else could capture the unique balance of empathy and dark humor that he brings to even the most monstrous characters. Solondz’s direction, along with the nuanced performances, invites a reflection on loneliness, desperation, and the often elusive nature of fulfillment. It remains a singular work, difficult to watch yet impossible to forget.

Special Features

This is a fairly disappointing showing from Criterion on the special features front, as only two new features are included: A pair of newly recorded interviews with Dylan Baker and Todd Solondz (the latter conducted by ex-student and director of Aftersun, Charlotte Wells).

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts