Elaine May is one of the great cautionary tales of film directing – having made three incredibly accomplished films, she made one flop (albeit one of the biggest flops of all time, the disaster that is Ishtar) and then was put off directing, seemingly for good. While The Heartbreak Kid and A New Leaf are both exceptional films, for me, Mikey And Nicky is her masterpiece. Ostensibly a gangster movie, it transcends genre to become a raw, intimate examination of male friendship—especially those bonds forged in childhood and tested by time and circumstance.

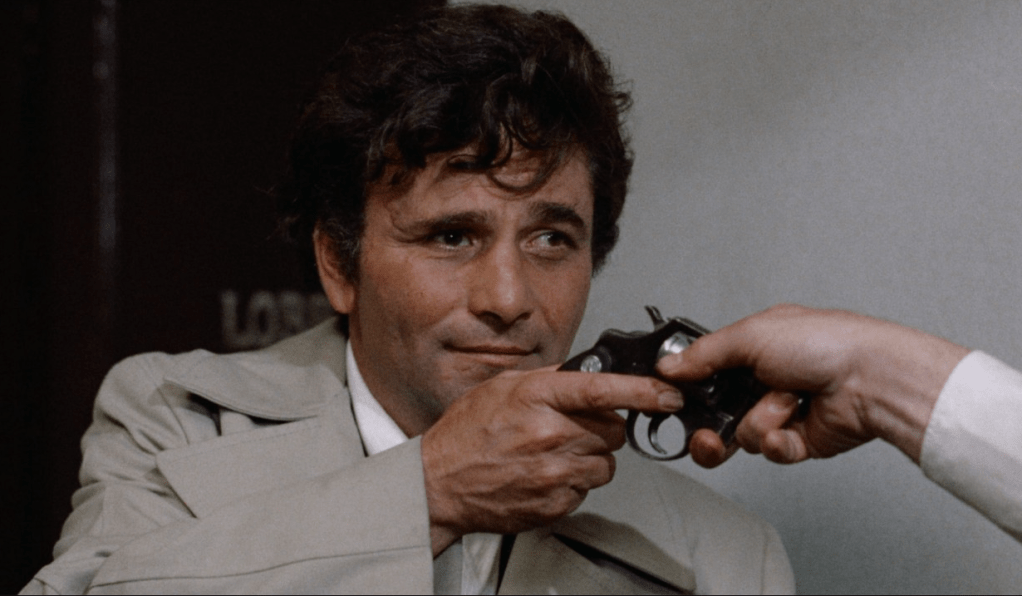

The premise is deceptively simple: Nicky (John Cassavetes), a low-level gangster, hides out in a dingy hotel room, paranoid that a hit has been ordered on his life. In desperation, he calls on his oldest friend, Mikey (Peter Falk), for help. However, in what Quentin Tarantino described as “one of cinema’s most devastating reveals”, it soon transpires that Mikey himself has been recruited to finger Nicky for the mob’s hapless hitman (Ned Beatty). This betrayal is disclosed early, and the rest of the film unfolds as a series of petty arguments, shared memories, and moments of tenderness between the two men.

The casting is impeccable. Cassavetes and Falk’s genuine off-screen friendship lends authenticity to their incredibly natural performances. They have an easy chemistry together that brings a lived-in quality to the character’s relationship. Cassavetes plays the volatile Nicky with a complexity that reveals warmth beneath his erratic, self-destructive exterior. He masterfully conveys Nicky’s oscillation between charm and chaos, and utterly nails those moments where he just turns on a dime. There’s one drawn out shot of Cassavetes just looking at Falk, making his growing suspicion apparent without uttering a word.

In contrast, Falk’s portrayal of Mikey is more subdued but equally layered, capturing a man torn between loyalty and obligation. When he urges Nicky to get to the airport and leave town, is it a genuine plea or is he simply playing the part of the loyal friend?

There’s a moment where Mikey talks about his deceased brother, and Nicky’s casual acknowledgment prompts a flicker of emotion across Mikey’s face. Though it’s only for a moment, you immediately understand what’s going on in his head. That quote from Hemingway about “Every man has two deaths: when he is buried in the ground and the last time someone says his name.” Mikey realises that by setting his friend up for murder he’s permanently severing a tangible connection to his past. Falk plays it beautifully, and it’s brought up again in the later scene with his long-suffering wife (played beautifully by Rose Arrick) as he tries unsuccessfully to replicate the kind of relationship he has with Nicky. It’s one of the most relatable scenes of the whole film, as he realises that his shared history with Nicky is something that he won’t ever have with anyone else.

May’s script is also deceptively complex. The dialogue between Mikey and Nicky is so prosaic, so repetitive, and yet the rhythm of these exchanges transforms the banal into something profound. The characters’ conversations reveal a long history of shared grievances and fragile bonds. May essentially defies you to like the main characters. Nicky is shown to be deeply misogynistic, racist, and cruel, while Mikey, though outwardly calmer, harbors insecurities and resentments of his own. Their visit to Nicky’s mistress (Carol Grace) is one of the film’s most deeply uncomfortable scenes, forcing viewers to confront the characters’ darker sides without apology or redemption.

Quentin Tarantino sums the film up perfectly, when he talks about the dramatic structure, and the shifting allegiance of the audience which mirrors the emotional tug-of-war between the characters themselves. Nicky initially earns our sympathy, purely because his situation is so desperate while Mikey’s betrayal makes him contemptible. Yet as the story unfolds, May deftly reveals how unworthy of Mikey’s loyalty (or our sympathy) Nicky really is, and Mikey’s internal conflict, leading to a gut-wrenching climax where the lines between victim and villain blur.

It’s also, it has to be said, very very funny. Again purely due to the interactions between Falk and Cassavetes, and the script, full of non-sequiturs and mundane remembrances, along with offhand remarks and playful taunts that feel incredibly authentic. The actors embody two lifelong friends, constantly needling each other, laughing at completely inappropriate injokes, and mothering each other. (Falk’s rapidfire delivery of “Didn’t I tell you to eat something in the bar goddamn you?” makes me laugh everytime). This humor amplifies the tragedy of the final scenes, making them resonate even more deeply. That argument scene, perhaps the standout scene in the film, makes an impression because the pettiness of the argument is so relatable, based off long-held resentment that exists between the two characters. It’s such a modern depiction of an argument that wouldn’t be out of place in The Sopranos (specifically in the episode Cold Cuts, where the two Tonys and Christopher are sharing jokes, only for the mood to be ruined by the emergence of deep-seated resentments that exist between the cousins) and yet it’s still so funny. Nicky shouting “That joke was for you!!” is funny precisely because the argument is so prosaic.

Some may be put off by the meandering story and the admittedly loose filming style, and it’s true that May seemingly has little interest in continuity or match-cuts, but while it may look a little messy, it’s a meticulously structured film, with several moments that pay off across the film. For example, the film is bookended with Mikey and Nicky trying unsuccessfully to break down a door – one is played for laughs, the other for pathos. Similarly, Mikey calls Nicky a schmuck in their first and last scenes together, but while the first is him berating his friend in an affectionate way, his resigned delivery of “Run, schmuck” in the final scene is almost as devastating as Cassavetes’ powerhouse performance. We should vilify Mikey for his actions, but we don’t. Similarly, the scene where Nicky says goodbye to his wife (Joyce Van Patten) and his baby doesn’t redeem him, but it is genuinely affecting. May never reconciles the antithetical reactions we have towards her characters. Instead the film leaves us with an uneasy feeling of moral uncertainty.

Mikey And Nicky is an often uncomfortable, sometimes painful viewing experience. Ultimately, the film captures the essence of a friendship steeped in both love and resentment—the kind that can make you laugh harder than anyone else but weigh you down like no other. May’s direction combines humor, pathos, and tension into a story that speaks to the complexity of friendship, loyalty, and memory. It is simultaneously a tragic tale of betrayal and a darkly funny meditation on the bonds that shape our lives. Genuinely essential viewing.

Special Features

This director approved release from Criterion looks stunning, regardless of the often disorienting shooting style. Extras include a new program on the making of the film featuring interviews with distributor Julian Schlossberg and actor Joyce Van Patten; new interviews with critics Richard Brody and Carrie Rickey; audio interview from 1976 between Schlossberg and Peter Falk.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts