Jean Eustache’s The Mother and the Whore has long been a cinematic white whale— notoriously unavailable for decades and shrouded in an almost mythical reputation. As such, it’s the perfect candidate for the Criterion treatment, and this release doesn’t disappoint. It’s a challenging film to watch, especially in today’s world where it’s nigh on impossible to fully immerse yourself in a film at home without distractions, and at 222 minutes, it’s undeniably a daunting commitment, but those who invest their time will be rewarded with a film that is an alternately witty, incisive and strikingly potent snapshot of an underrepresented period in France’s history.

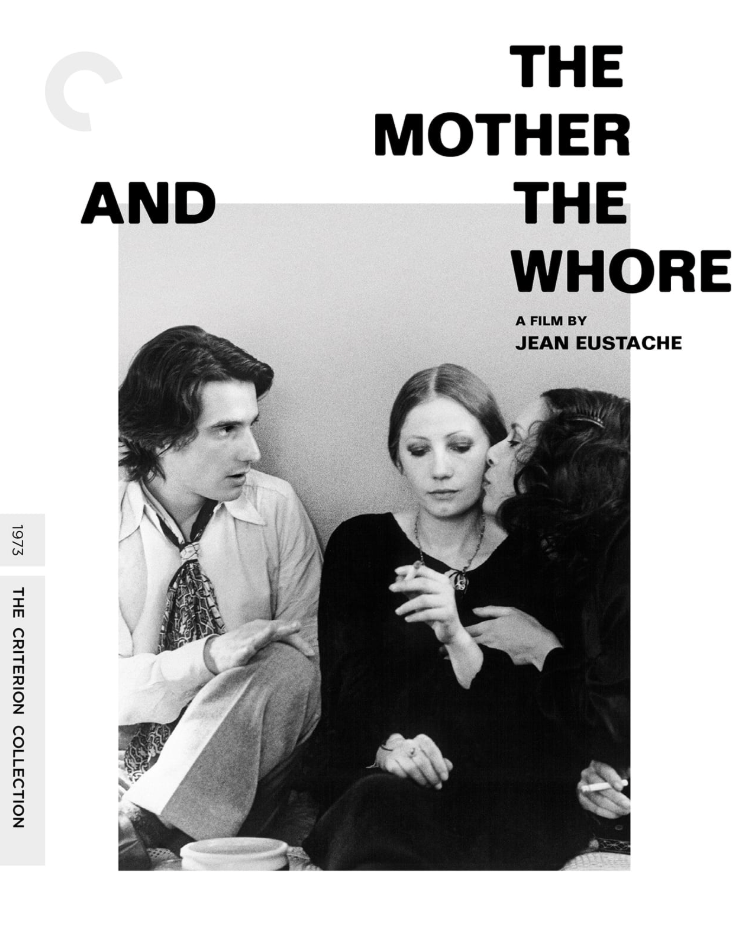

Set in post-1968 Paris, the film unfolds through a series of extended dialogue scenes, following the life of Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a self-absorbed pseudo-intellectual who spends his days reading in cafés, (emphatically *not* writing) flirting with women, and borrowing money, and his nights at the apartment of his sometime lover, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). The arrival of Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a liberated and unapologetically candid nurse, brings not entirely unwelcome complications into his life, drawing the three into an uneasy and ultimately destructive ménage à trois.

It’s a film full of contradictions – heartfelt and satirical, ironic without being cynical, ahead of its time and distinctly of its time, espousing liberal ideas and yet couching them in a pervasive kind of patriarchal oppression. The entire film is an unflinchingly honest document of the malaise that emerged in the wake of the civil unrest of 1968, and this is best demonstrated through the characterisation of the disenchanted, untethered younger generation.

Alexandre himself fancies himself a modern man, embracing progressive ideas on the surface, yet his relationships are steeped in the patriarchal expectations he claims to reject. The title is both ironic and revealing, reflecting the roles he imposes on the women in his life. Marie, cast as the “mother” figure (despite being only 30!) provides domestic stability, and Veronika, whom he labels, implicitly and explicitly, as the “whore” for her sexual freedom and lack of inhibitions.

Eustache’s female characters are where the film truly shines. Lebrun’s Veronika, candid speech and raw vulnerability, emerges as a complex and heartbreaking figure. Her climactic monologue, delivered in an unbroken take, is one of the most searing indictments of societal and relational hypocrisy ever committed to film. Lafont’s Marie, too, brims with quiet strength and frustration, her interactions with Alexandre exposing the power imbalances and contradictions inherent in their relationship. Viewed through a modern lens, both women are strong, independent characters trapped within the oppressive gender dynamics of their time, and Eustache captures this tension with unflinching clarity.

At nearly four hours long, the film is a bit of an endurance test, however despite this, (and the fact the film itself is essentially a series of long conversations), it largely avoids the tedium of something like Jeanne Dielman. While there isn’t much action or forward momentum, there is a real vitality and a palpable drama underpinning every interaction, rooted in Eustache’s deeply autobiographical script. He gives a startlingly self effacing, brutally honest account of himself, with candid dialogue that is punctuated with moments of genuine pathos. Alexandre’s monologue about an ex-girlfriend’s abortion, delivered directly to the camera, is a standout moment, showcasing Léaud’s ability to humanize even the most frustrating aspects of his character.

Stylistically, The Mother and the Whore functions as both an homage to and an affectionate pastiche of the French New Wave. While it lacks the youthful energy of early Nouvelle Vague films, it offers a more sophisticated and self-aware take on the movement’s themes, both embracing and transcending the movement’s stylistic and thematic aesthetics. The film’s ironic callbacks to classics like Francois Truffaut’s Jules et Jim underline its position as both a culmination and a deconstruction of the era’s cinematic ideals. As well as offering a much more realistic depiction of a menage-a-trois, in one memorable scene, Veronika sings for Alexandre in her apartment, echoing Jeanne Moreau’s iconic performance in Jules et Jim, only for Alexandre to abruptly turn on the radio when she finishes. It’s a quietly devastating critique of his unwillingness, or inability, to engage emotionally. It’s no wonder that Cahiers du Cinéma named it the best film of the 1970s.

The casting of Léaud as Alexandre is particularly inspired. Having risen to prominence as the face of the French New Wave in films like The 400 Blows and Stolen Kisses, Léaud brings an almost meta quality to this subersion of the New Wave male archetype. He’s consciously depicted as a narcissistic facsimile of the roguish protagonists of the nouvelle vague; charming, well-read, and effortlessly romantic but also selfish, hypocritical, and emotionally detached. He would be utterly unbearable if his intellectual posturing wasn’t consistently punctured by Eustache’s sharp writing. As it is he emerges as a pathetic figure, and in the end he is a lot more endearing than even he would like to be.

It’s not a comedy, and it’s not particularly funny, but it’s a beautifully complex character study, and oddly ahead of its time in its portrayal of a very specific kind of toxic masculinity. It’s apt that both Mikey And Nicky and The Mother And The Whore have been released by Criterion in the same month, as both feel influenced by John Cassavetes. Elaine May clearly took at least some elements from Cassavetes’ style in her film, while this feels like another antecedent of his work in its nuanced, authentic representation of human relationships.

Unlike something like, say, Seven Samurai, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel the runtime of this one. It’s a demanding film, but one that rewards the audience’s patience, and the result is a nuanced exploration of the often contradictory and oblique nature of human relationships. Crucially, while I have no wish to put myself through Jeanne Dielman again, I will almost certainly revisit this one in the future. There’s something almost intangibly appealing about the characters and the setting that evokes a very specific period in France’s history. It’s deeply rooted in its time while addressing timeless themes of alienation, desire, and societal disillusionment.

The Mother and the Whore is a film of extraordinary complexity, at once brutally honest and achingly tender. It offers up a scathing yet empathetic portrait of masculinity, love, and the shifting cultural landscape of 1970s France. It’s an incendiary confrontation with the messy, contradictory nature of intimacy and identity, and the gender dynamics that unfortunately still persist today. This restoration ensures that Eustache’s masterpiece remains a vital work for modern audiences, cementing its status as one of cinema’s most profound achievements.

Special Features

This new restoration of the the black and white film looks incredible, offering a restoration that preserves the sharp, inky richness of Pierre Lhomme’s 16mm cinematography. The extras include a new interview with Françoise Lebrun, a conversation on the film with filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin and writer Rachel Kushner, a feature on the restoration of the film, and a segment from the French television series Pour le cinéma featuring Lebrun, Jean Eustache, Bernadette Lafont and Jean-Pierre Léaud

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts