In the wave of hyperbolic praise surrounding the release of Osgood Perkins’ Longlegs last year, one detail stood out to me. It wasn’t the inevitable “scariest film ever” soundbites, but rather the comparisons critics made to Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure, a quietly devastating psychological thriller that continues to haunt audiences decades after its release.

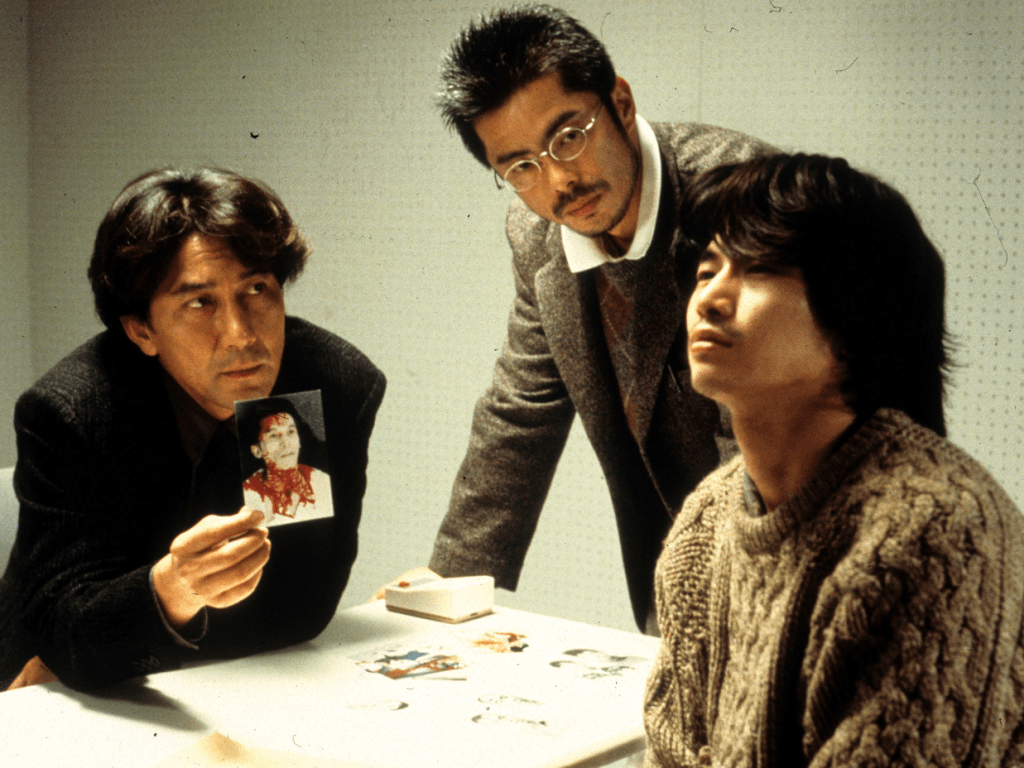

Cure immediately establishes its tone with a disturbing juxtaposition in its opening scene: a disturbing juxtaposition: a man nonchalantly bludgeons a sex worker to death with a pipe, cleans up, and showers, all set to an oddly upbeat soundtrack. It’s soon revealed that this is the latest in a spate of murders, each committed by different people who have no connection to one another, and no memory of their crimes. The only common thread is a grisly X carved into the victims’ necks and chests, ominously prefigured by the murderers painting giant X’s on their walls while in a trance. Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) and criminal psychiatrist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) investigate, eventually encountering Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), a young, enigmatic drifter who has spoken with each suspect and seemingly influenced them into committing murder. Mamiya seems to not know who or where he is, and his sole form of communication is asking apparently innocuous questions – a quirk that begins as faintly amusing but grows increasingly sinister as the film progresses.

At first glance, Cure unfolds as a stylized psychological thriller with a familiar setup. Takabe’s personal stress, stemming from his wife’s deteriorating mental health, (she is often found wandering around, lost, in a nod to Makoto Shinozaki’s Okaeri) adds a layer of human vulnerability to the narrative, as well as establishing him as a moral centre for the story. But as the possibility arises that Mamiya’s hypnotic influence might extend to Sakuma—or even Takabe himself—the film shifts gears, transforming into a chilling horror story where hope diminishes with every passing scene.

This transition is mirrored in the film’s pacing and tone. The brisk investigative rhythm of the first half slows dramatically once Mamiya is in custody, with measured, abstract sequences reflecting Takabe’s unraveling mental state. Kurosawa’s restrained editing heightens this tension, interspersing sporadic bursts of violence that suggest that Takabe’s own soul is at stake. This culminates in a hauntingly ambiguous final scene – a subtle yet shattering conclusion that lingers in the mind long after the credits have rolled.

The film’s grim narrative is masterfully supported by its visual and auditory design, beautifully rendered in this UHD release. Kurosawa frames characters with deliberate distance – partially obscured or positioned in wide, detached compositions – creating a sense of alienation. The neutral, washed-out color palette lends a clinical coldness to the violence, which is depicted with a disturbing calmness. Similarly, the gore is presented subtly, but with unflinching precision, such as the horrifying scene where a flap of skin is peeled back over a victim’s face. A droning, almost imperceptible soundtrack amplifies the film’s hypnotic atmosphere, subtly aligning the audience with the victims’ growing unease.

Kurosawa’s genius lies in how he refrains from spoon-feeding the audience. Instead, he uses sound design, framing, and editing to build a pervasive sense of dread. Moments of revelation often unfold subtly in the background, such as a character casually revealing a painted X on his wall—a harbinger of doom—before absent-mindedly scrubbing it away. This careful, restrained approach pulls the viewer into the film’s unsettling rhythms, making us question not only the characters’ morality but also our own.

The closest western equivalent to Cure’s conclusion might be David Fincher’s Se7en. Indeed Yakusho’s performance is very similar to Morgan Freeman‘s Detective Somerset. Both actors imbue Takabe with a world-weariness and dignity and sense of gravitas that makes him seem such a pillar of decency.

However, even Se7en’s grim finale offers a sense of moral resolution. Justice – well, call it a pyrrhic victory – prevails, and Somerset emerges with his principles intact. By contrast, Cure offers no such solace. Its ending denies catharsis, leaving us to grapple with the uncomfortable notion that Takabe may not be the moral anchor we hoped for.

Unlike Se7en, the perpetrator in Cure is not himself a murderer – indeed he never lays a finger on anyone – but in Kurosawa’s hands the simple act of sparking a lighter is given a dreadful significance. As Mamiya, Hagiwara gives a wonderfully enigmatic performance. He doesn’t play him as evil, or sinister, or flamboyant. He seems perpetually distracted, too unfocused to be a threat, and yet he is incredibly disconcerting. He’s introduced standing in the distance on a beach, staring into the distance, until his gaze fixes on the camera, and the unsuspecting bystander who happens to have caught his eye. It’s a chilling way to introduce the character, and his sudden appearance (he seems to just apparate out of thin air) gives him an ethereal quality. Cure challenges our deeply held belief that only “bad people” are capable of murder. Kurosawa suggests that the potential for violence resides within us all, lurking beneath layers of repression and civility. By the film’s end, even the seemingly moral Takabe appears fallible, leaving us with the chilling realization that no one is immune to the darker forces Mamiya represents.

Kurosawa’s later films, such as Pulse and Tokyo Sonata, share his signature preoccupation with existential despair, but Cure is his most nihilistic film. The film’s bleakness is absolute, its vision of humanity as unsettling as it is unforgettable.

With Cure, Kurosawa holds up a mirror to our darkest selves, forcing us to confront the destructive impulses we’d rather ignore. It’s a filmic poem of quiet devastation—a deliberate, hypnotic meditation on violence, morality, and the fragility of the human psyche. It’s one of my favourite films of all time, a sparse, thematically dense thriller that leaves you with a feeling of unshakeable disquiet, and pretty much a perfect film.

Special Features

Extras include two interviews with Kurosawa on 2003 and 2018; an interview with author and horror expert Kim Newman, and trailers.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts