I had a vivid dream the other day. (It’s a strange way to start a review but bear with me.) I was walking my son to school with my brother, and when we got to the building, my brother went in ahead of me, but then quickly ran back out and said just one word: “Run.” That’s when I woke up. Even after realizing it was all a dream, the feeling of dread lingered all day. I had that same feeling of apprehension, a creeping sense of danger, while watching September 5, a film that immerses you so fully in its unfolding crisis that the weight of history and the unpredictability of the moment feel crushingly real.

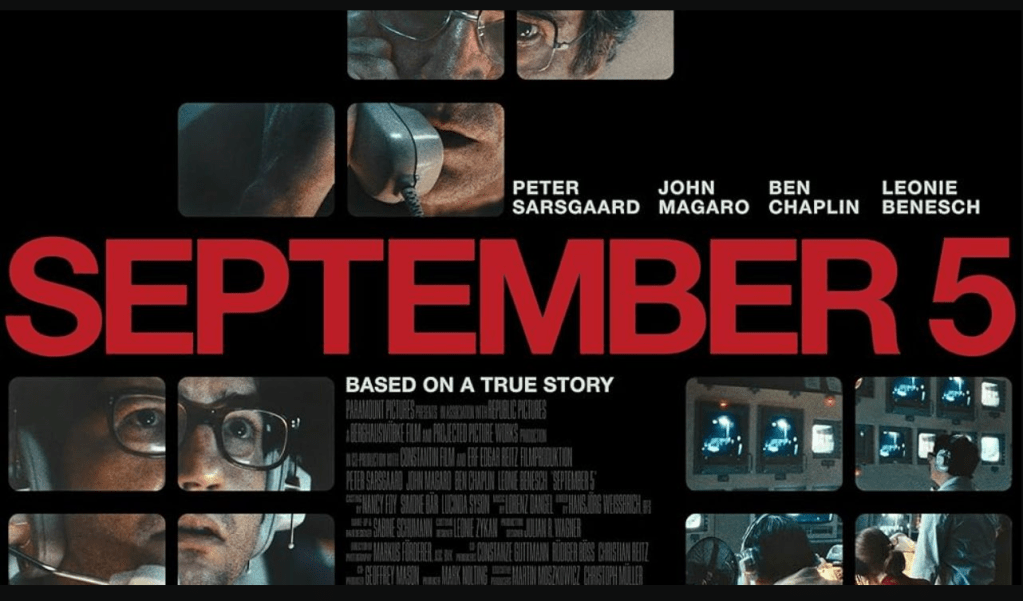

A gripping portrayal of the 1972 Munich Olympics terrorist attack, Tim Fehlbaum’s film offers an unsanitized, non-judgmental look at the tragic events from the perspective of the ABC newsroom reporting on the rapidly escalating hostage situation. By throwing the audience into the midst of the action, Fehlbaum creates an immersive experience that is both suspenseful and thought-provoking. Even knowing the historical outcome, the film retains its ability to shock, much like the real-life events it depicts.

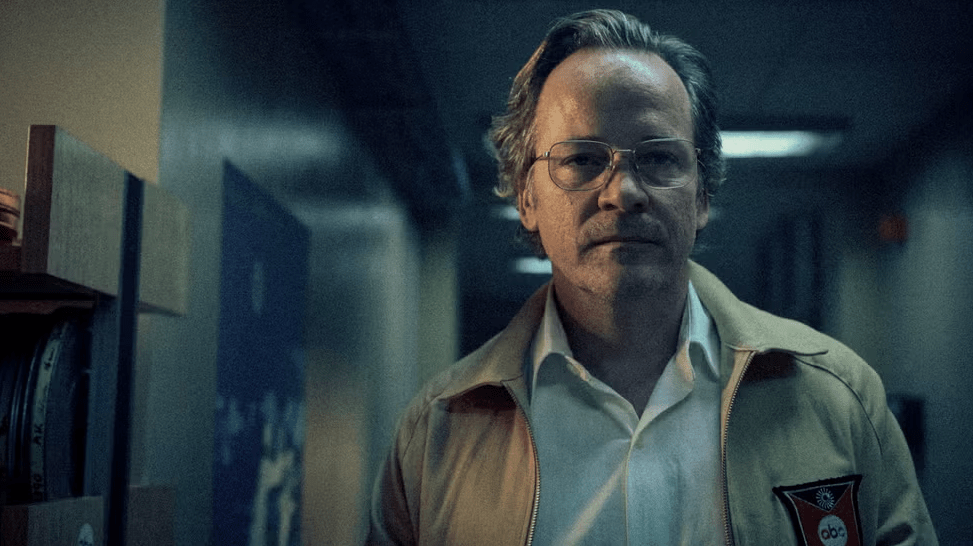

Our window into this world is the untested studio director played by John Magaro, trying to prove himself to the unconvinced TV exec (Peter Sarsgaard) while finding himself increasingly out of his depth as the crisis escalates. Sarsgaard himself is positively reptilian, channeling both Philip Seymour Hoffman and John Malkovich with his dishevelled appearance and the sardonic curl to his lips. He remains coldly pragmatic about the situation, contrasting sharply with the more ethically conscious producer played by a virtually unrecognisable Ben Chaplin. At the films critical point, these two serve as the angel and demon on Magaro’s shoulders, each one pushing him to make a decision that could have consequences.

Most impressive of all is Leonie Benesch, playing a fictionalised character who nevertheless embodies a necessary perspective in the film; that of a representative of post-war Germany. She is the interpreter who is recruited to translate the various announcements in German, often in makeshift ways – having to hold the phone received up to a walkie talkie, for instance. She utterly nails her characters shock, yes, but even more impressively, the crushing disappointment of being a German once again seeing their country in the news for the wrong reasons.

What makes September 5 particularly striking is its historical proximity to World War II. It’s easy when watching something set in the distant past, to imagine that each of these historic events existed in a vacuum, and you forget that in 1972, the Second World War was still very much in the forefront of everybody’s mind. Fehlbaum highlights how, for the Americans, the German characters are still closely associated with the war – this is shown early on when Chaplin’s character makes a prejudiced comment, then immediately apologizes – while for the Germans, these events threaten to undo years of effort to move forward. This added historical context serves as a quite poignant beat for Benesch’s character, but also explains the dithering of the German police later in the film, and their determination to find a positive spin on the unfolding crisis.

Unlike more dramatized depictions such as Munich, Fehlbaum’s film avoids contrivances and reworkings of the facts. Rather than indulging in overwrought melodrama, September 5 presents the events of the film through a coolly detached, often nonchalant lens, which only serves to deepen the impact of the tragedy. The seamless integration of real-life archival footage with the film’s narrative adds to its documentary-like authenticity, reinforcing the stark reality of the events. Fehlbaum even utilises footage of real-life reporters Jim McKay and Peter Jennings, who interact with the films’ characters in a way that doesn’t feel showy and only enhances it.

Fehlbaum’s restrained direction refuses to sensationalize the violence, opting instead for a raw, unfiltered portrayal of the events. He pointedly refuses to get into the action itself, restricting the film’s scope to the studio gallery, and by doing so—in a counterintuitive way—heightens the tension. Audiences rarely find themselves in the midst of a shootout, but who hasn’t had that horrible sinking feeling when something is happening just down the street from them? The moment when a terrorist leans out of the hotel room, looking directly into the camera, is chilling in its simplicity.

One of the film’s strongest elements is its exploration of the media’s role in reporting on the crisis. The tension between the news and sports divisions is given perhaps more weight than it warrants – when lives are at stake, who really cares which department reports it? The film doesn’t exactly lionize the press (Sarsgaard is particularly repellant) but there’s a whiff of Aaron Sorkin like self-aggrandizement, reminiscent of The Newsroom, where journalists seem to take undue credit for historical events.

In fact the film is at its most provocative when delving into the ethical dilemmas faced by the TV crews. The implication that the terrorists are watching the footage that the sports team are broadcasting raises the question of what exactly the medias responsibility is in this situation. By broadcasting live footage, were they aiding the terrorists as much as they were informing the public? A particularly striking moment is when Chaplin’s character asks, “Whose story is it? Ours or theirs?” It’s a moment that stops the frantic action of the film dead, and offers a sobering insight into the motives behind reporting, and the fine line between news and spectacle.

With its restrained storytelling, ethical quandaries, and immersive newsroom setting, September 5 stands as a powerful, small-scale examination of a pivotal historical moment. Its refusal to editorialize or sensationalize makes it a haunting and thought-provoking watch, and despite being much smaller in scale than the usual prestige true life dramas, there remains a palpable tension. It’s not jingoistic or maudlin, it simply presents the events with a dispassionate eye and is all the more affecting for that.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts