Nacho Vigalondo has always been a director more interested in form than content, consistently pushing cinematic boundaries. At his best, he is able to blend his experimental approach with emotionally grounded storytelling, such as in his previous film, Colossal. Even his weaker efforts, (looking at you, Open Windows) burst with undeniable creativity. Daniela Forever continues this trend, delivering a visually inventive yet tonally uneven meditation on grief, memory, and control.

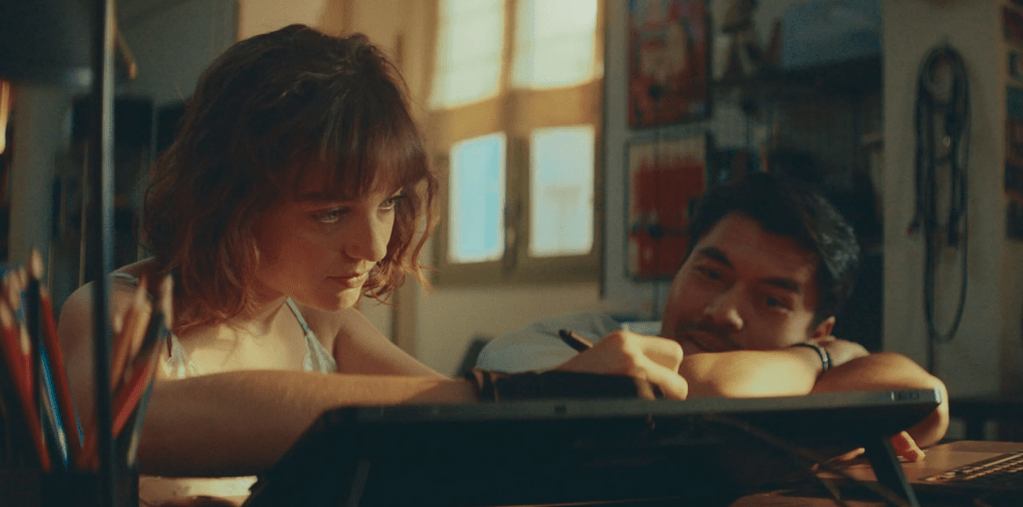

With echoes of Michel Gondry and Christopher Nolan, Daniela Forever tells the story of Nicolas (Henry Golding), a man devastated by the death of his partner, Daniela (Beatrice Grannò). Distraught and unable to sleep, he submits himself to an experimental technology that should help him have lucid dreams that will help him through his grief, but with strict parameters – he must follow the cue cards that will inform his dream environments. However, in an attempt to see Daniela again, he disregards the rules and instead dreams about her. He soon withdraws almost entirely into this dream reality, creating problems that extend beyond his own mind, with implications on the real world.

Vigalondo’s world-building is impressive, crafting a setting that feels both intimate and immersive. The blurred visual effects that signal Nicolas’ entry into the dream world and the “unfinished” quality of unfamiliar settings are well-executed, evoking comparisons to Inception and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Fittingly, considering Nicolas’ depressed mindset, the real world is presented as drab documentary style 4×3 aspect ratio, with natural, muted lighting, while the dream world, where he can live his best life with Daniela, is shot in lush widescreen, with vibrant colours. This distinction is so marked that when the lines between the two begin to blur, it is genuinely disconcerting.

At its best, the film explores the unhealthy side of grief. Initially, Nicolas’ use of the technology is generically wholesome – he gets to spend time with Daniela again, and everything is saccharine and sweet. But before long, his interactions with her dream version become increasingly uncomfortable. It’s almost funny how quickly the film changes tack from “I get to spend more time with my deceased partner” into essentially holding his partner hostage. His need for control takes over, and he holds her captive in his mind, forcing her to enjoy hobbies she never cared for. His jealousy even extends to Daniela’s dream-world friendships, revealing an insecurity that turns him into an emotionally stunted man-child rather than a grieving lover. Golding plays all of this really well, and despite feeling miscast in the role, he performs the less attractive facets of his character with an admirable lack of vanity.

This darker exploration of grief recalls Truly Madly Deeply, particularly in the scenes where Juliet Stevenson’s character gets a bit fed up with the ghost of her partner (Alan Rickman) just having his friends over and generally being in her space all the time. However, where that film acknowledged the reality of moving on, Daniela Forever lingers on the possessiveness of clinging to an illusion. Nicolas’ grief journey is, in many ways, selfish—his version of Daniela lacks true agency, existing only as a facsimile he manipulates to fit his desires. This unsettling dynamic offers some of the film’s most interesting but jarring moments, especially when he rewrites her personality to be more subservient, or fast forwards her agonizingly drawn out confession.

Remember in Inception, where it turns out that Leonardo DiCaprio and Marion Cotillard grew old together in limbo, creating worlds together for decades? That’s a beautiful idea, but it doesn’t work if only one of them has autonomy. Here, Nicolas is all-too aware that he is the “real person” in his dreams, and the way he uses this position of power is often really uncomfortable. This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, but the film never really addresses his controlling behaviour, which leads to a pretty uneasy viewing experience, and an ending that just doesn’t resonate on an emotional level.

Despite its strong thematic core, Daniela Forever struggles with pacing. While the world is intriguing, the story often feels immobile, failing to maintain momentum. Yet, the film has moments of inspiration, none more so than the surreal “shark with a gun” scene, which provides a brief jolt of absurdity and much needed comic relief.

In a poignant touch, we see that Nicolas is unable to fill in the blanks of locations he hasn’t visited before in his dreams. As such, and in an attempt to connect further with Daniela, he visits new places, and takes an interest in her passions, so she can enjoy them again in his dreams. He inadvertently pushes himself to experience new things in his real life that Daniela liked, things that he never really took much time to experience before. In these instances, we see a glimmer of something truly affecting: the idea that true love isn’t about possession, but about shared experiences and growing together. This is a really interesting, touching subplot, and you might think it would lead to him forming a stronger bond with Daniela than when she was alive. Unfortunately this idea is hastily discarded as the film reaches it’s messy, nigh on incomprehensible conclusion.

Ultimately, Daniela Forever is a fascinating but flawed film. It offers kernels of brilliant ideas but doesn’t fully capitalize on its unconventional premise. While it succeeds in presenting a unique take on grief, it falls short of delivering a fully satisfying emotional payoff, largely due to the unsympathetic character at its centre. Nonetheless, it’s an intriguing entry in Vigalondo’s filmography—one that may not be perfect, but is certainly worth a watch.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts