There have been a few films that tackle weighty issues through the lens of a child’s perspective, often choosing one of two approaches: either an overly stylized, fairy-tale-like presentation (Pan’s Labyrinth, Tideland) or a stark, unflinching realism (Ratcatcher, The Florida Project). The final film in our coverage of the Glasgow Film Festival, Spilt Milk manages to have it both ways, while still maintaining a consistent tone – just about.

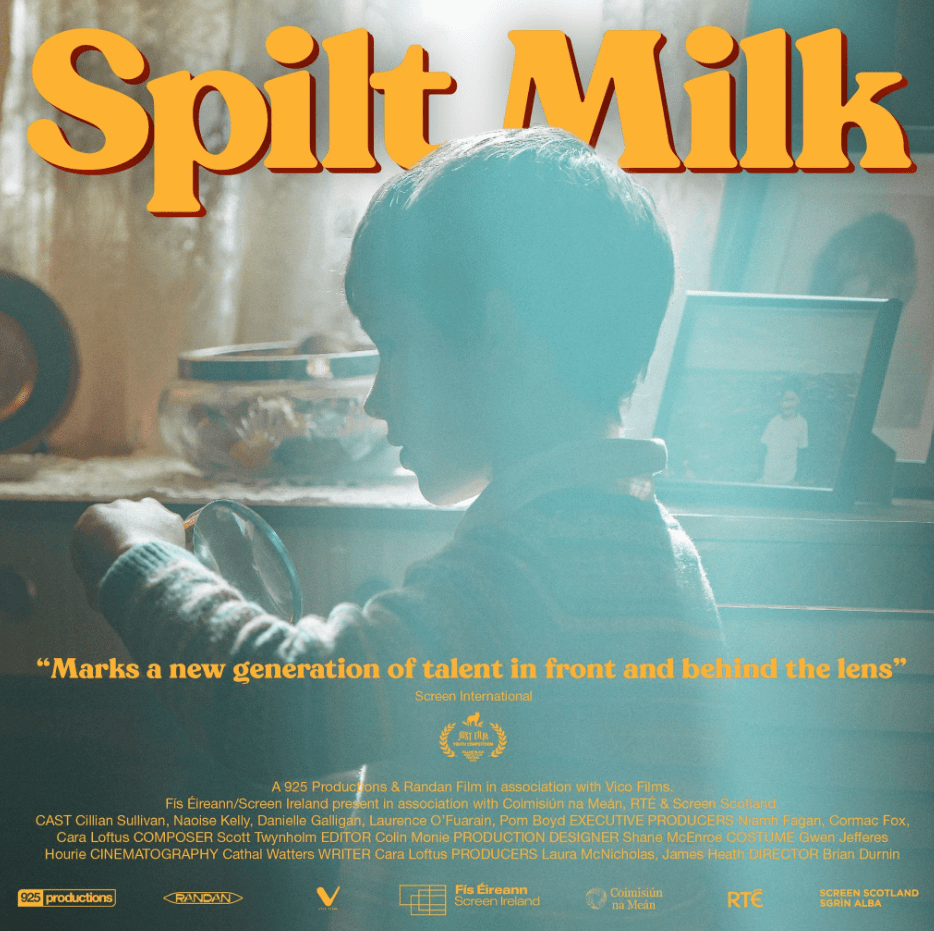

The directorial debut of Brian Durnin, Spilt Milk is an ambitious coming-of-age detective story following 11-year-old Kojak superfan and budding sleuth Bobby O’Brien (Cillian Sullivan). The film introduces Bobby having solved a slew of minor mysteries – mainly missing pets – around the housing estate with his best friend Nell (Naoise Kelly). However, Bobby soon finds himself out of his depth when he takes on a much more serious case – the disappearance of his older brother Oisin (Lewis Brophy) after a heated row with their father (Laurence O’Fuarain) As Bobby digs deeper, he stumbles upon something far more insidious lurking in mid-80s Dublin.

Tonally, the film shares DNA with Evan Morgan’s The Kid Detective, albeit with a very different focus. Like that film, Spilt Milk begins with a sense of quirky, almost playful intrigue before veering into much darker territory. The shift in tone, while largely effective, is initially a little jarring.

At the heart of the film is the friendship between Bobby and Nell, whose chemistry feels effortless. Their interactions shine with authenticity, free from any forced “child actor” mannerisms, and Nell’s ever-present hunger—she’s eating in nearly every scene – is an endearing character trait / running gag. There are a few moments where the blocking feels muddled, or they stumble on their lines, but you get the distinct impression that maybe the child actors got a bit carried away, and in any case it all adds to the authenticity of their performances.

The portrayal of Bobby’s parents is another of the film’s strengths, with both actors delivering layered, believable performances. O’Fuarain’s John isn’t simply a stereotypical working-class father; he clearly loves his family, even as he loses patience with his eldest son. His exasperation with Bobby’s detective obsession is more good-natured than truly harsh, though his flashes of anger at Oisin are more concerning. As the long-suffering matriarch of the family, Danielle Galligan, however, quietly steals the film. She conveys a deep well of pain and resilience, particularly in a devastating early scene where she picks up an old jumper of Oisin’s. By the film’s powerful climax, she delivers a monologue that, in lesser hands, could have felt preachy – but instead lands as raw and deeply affecting.

Durnin’s direction is subtle yet considered. Early on, he presents the world through Bobby’s childlike perspective, complete with a whimsical title sequence and a cutesy introduction to his minor cases. It borders on twee but never loses sight of the film’s sense of realism. As Bobby’s innocence fades, so does the film’s playful aesthetic, shifting toward a starker, more gritty style. The transition is admittedly a little jarring, but Durnin expertly heightens the tension as Bobby steps into the dangerous world of drugs and crime. You know, logically that he’s not going to take the film in too dark a direction, but there’s a palpable sense of danger in the scenes where Bobby enters the much harsher world of drugs and criminality.

While the tonal shift might initially feel abrupt, Durnin lays the groundwork early, planting subtle clues – like the mystery of Maura’s missing wedding ring and the stolen television – that gradually reveal the film’s true trajectory. It’s structured in such a way that it becomes apparent to the audience what’s going on just before the children, and there’s a genuine poignancy in that brief crossover, where Bobby and Nell still think this is a standard mystery to be solved, while we already understand the grim reality – Oisin has fallen victim to the epidemic of heroin addiction that devastated Dublin in the 1980s.

Durnin gives the film a real identity – placing it very deliberately in a specific time and place. He captures the sense of community, the ineffective police force and the extended family that exists among the neighbouring families in the estate – both the warmth with which the families treat each other, and the building sense of sadness and despair due to the malignant presence of the drug dealers on the block.

An assured and affecting debut, Spilt Milk begins as a charming, low-stakes drama before evolving into a nuanced examination of a family torn apart by addiction, told with pathos and subtlety. It’s thematically weighty yet never heavy-handed, blending warmth and melancholy in equal measure. Adorable without tipping into whimsy, emotional without being manipulative, and just about avoids preachiness in its powerful conclusion.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts