“Look into my eyes, you’ll see trouble every day“

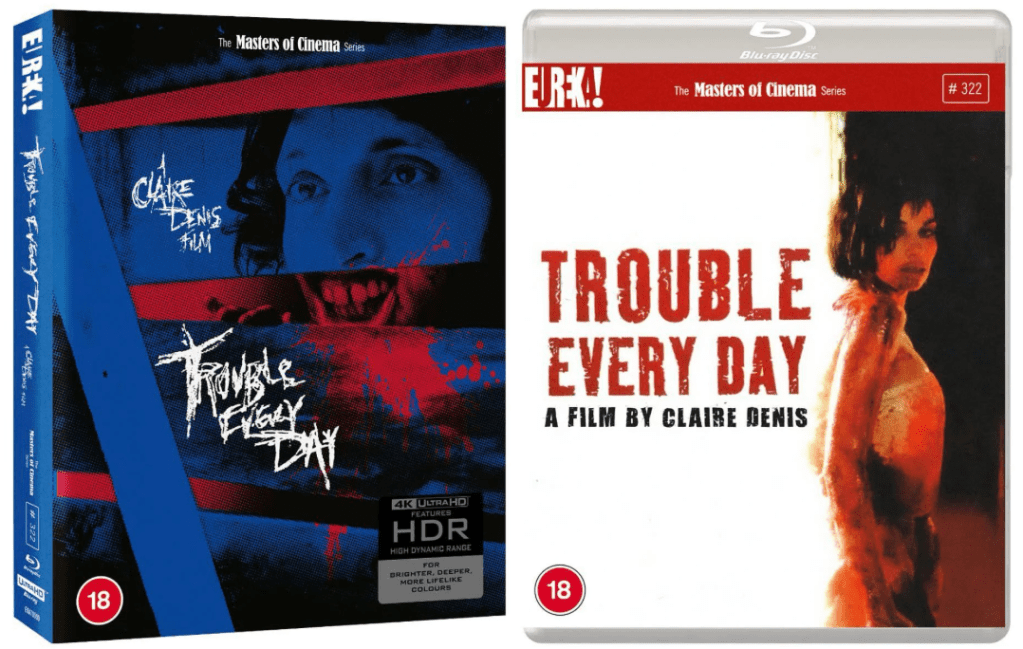

Trouble Every Day is a film I’ve wanted to see ever since I was a teenager first discovering international cinema. The film’s iconic promotional image – Béatrice Dalle, her mouth smeared with blood and viscera – seared itself into my brain and has never let go. Unavailable in the UK for a long time, Trouble Every Day has now received a Blu-ray release from Eureka films, and after years of anticipation it did not disappoint – though it is very much an acquired taste.

It’s acquired for two reasons. First, its subject matter: cannibalism, vampirism, sex, and violence, depicted in ways that are deeply uncomfortable. Second, because it is directed by Claire Denis, whose characteristically elliptical style defies traditional narrative conventions. She tells stories through images and editing rather than dialogue or plot mechanics. The result is a film that feels at once elusive and unforgettable, unlike any other horror you are likely to encounter.

American scientist Shane Brown (Vincent Gallo) travels to Paris with his new wife June (Tricia Vessey) under the guise of a honeymoon. But Shane has an ulterior motive: he is searching for a former colleague, Leo (Alex Descas) who he thinks holds the key to a strange, undefined affliction he suffers from. Leo’s wife, Coré (Dalle), shares the same condition – an uncontrollable urge to consume human flesh.

This “disease” is never explained in detail, nor does Denis appear to have much interest in conventional lore, or anything supernatural. Instead, cannibalism here functions as metaphor. Other directors have equated vampirism with addiction or illness — Abel Ferrara in The Addiction, Tony Scott in The Hunger. Denis, however, insists the story is really about love and desire: “It’s actually a love story… It’s not about cannibalism either. It’s about desire and how close the kiss is to the bite.” This statement emerges as the key to the film – consumption not as metaphor for disease, but as a grotesque extension of lust and intimacy. The act of biting victim’s necks has had the distinct feeling of a seduction, going all the way back to Bela Lugosi, and this is simply the same principle taken to extremes.

Denis isn’t above paying homage to genre cinema though, employing several playful allusions to Vampire cinema. Coré spreads her arms in her coat like a bat’s wings; Shane sleeps on a bench with his arms folded across his chest in a clear nod to Nosferatu. Leo’s ritual of cleaning up after his wife – tenderly bathing her after each murder – feels more like the work of a loyal familiar than a husband, recalling the caretaker roles in Let the Right One In or Eyes Without a Face. Most persuasive of all is the depiction of Christelle (Florence Loiret Caille) – the hotel maid Shane obsessively watches. She is constantly positioned as a victim, the camera focusing on the nape of her neck as Shane essentially stalks her throughout the film, until the final horrific attack – the one moment where Denis acquiesces to genre convention, allowing the horror to unfold in full.

Watching Trouble Every Day, it becomes clear that the violence stems from two very different kinds of desire. Coré’s compulsion is primal, tragic, and strangely tender. As Alice Haylett Bryan asserts in her incisive interview included in this release, Coré’s cannibalism is essentially a manifestation of a disturbing form of love. In any case it is made clear that she is utterly unable to control her impulses. By contrast, Shane, who is apparently in the early stages of the disease, represses his urges – but only just. Faint bite marks on June’s arm, and a fresh cut on her lip, suggest he’s already struggling to maintain control. Even early in the film, he gets Christelle in his sights, and there is the distinct feeling of a predator stalking his prey in their interactions. His urges are about domination and possession, culminating in an act of sickening brutality. Despite Coré’s graphic murders, it is Shane who emerges as the true monster, his sexual frustration manifesting itself in just about the most horrific way possible.

This contrast also inverts a classic horror dynamics. Instead of the promiscuous or “low-status” woman punished by the monster – a trope stretching back to Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Frankenstein – here the monster is the respectable man, hiding behind his honeymoon facade, stalking the vulnerable woman. Meanwhile, another “vulnerable” woman, is herself hunting and consuming promiscuous men — a dynamic reminiscent of Scarlett Johansson’s alien in Under the Skin. A definite precursor to Julia Ducorneau’s Raw and Luca Guadagnino’s Bones And All, Denis reframes desire as something inherently violent, and renders cannibalism as something intimate, melancholy, and strangely romantic.

Like Beau Travail before it and High Life after it, Trouble Every Day demonstrates Denis’ gift for combining beauty with ugliness. A scene of extreme gore will sit next to a beautifully depicted scene of a couple visiting Notre Dame Cathedral, and watching a scarf caught by the wind. She has a unique visual language that is equal parts entrancing and confounding, deploying long wordless passages and deliberate, lyrical shot choices. It makes for a hypnotic, and oddly enthralling experience.

It is easy to see why Trouble Every Day is often grouped with the New French Extremity, the wave of late-’90s and early-2000s films characterised by explicit depictions of sex and violence – usually a combination of the two. Denis certainly fulfils the label in the literal sense. Yet her approach is more nuanced than most. She refrains from depicting the violent acts themselves until late in the film, often only showing the aftermath. This restraint makes the eventual explosion of horror all the more shocking and upsetting.

This is why the label “erotic horror” does the film a disservice. There is nudity, there is sex, but none of it is titillating. Every encounter is filled with a dreadful anticipation of something unspeakable just around the corner. Denis balances cinematic beauty with deeply nasty horror, and it’s this contrast that makes the film such uncomfortable viewing. Denis makes the erotic horrifying, and the horrifying strangely intimate.

Much of this atmosphere rests on the actors. Béatrice Dalle gives a remarkable, largely non-verbal performance. She is a feral, primal presence in the film, and Denis emphasises her predatory nature in every frame, whether it’s the way she restlessly paces behind boarded-up windows or the intensity of her gaze on each potential victim. Vincent Gallo, meanwhile, looks perfectly suited to the role – gaunt, haunted, unsettling – but his performance is weaker. Still, this inadvertently works in the film’s favour, giving Shane a hollow quality and an emotional distance that underlines his predatory emptiness.

Trouble Every Day is not an easy watch but might be essential. It’s a deeply disturbing, yet fascinating film, lyrical, beautifully shot, and filled with moments of haunting tenderness to counter the gut-wrenching violence. It is not really horror, not really erotic, not really romantic – but contains elements of all three. It is its own unsettling hybrid, a film that only fully reveals its meaning in the days that follow, as the images settle and resurface.

Special Features

The extras include two newly recorded commentaries, one featuring Denis herself, the other from film critic Lindsay Hallam; an enlightening interview with Alice Haylett Bryan on the film’s status among the sub genre of New French Extremity films, and a video essay – Material Vampires and the Defeat of Science – from Virginie Selavy.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts