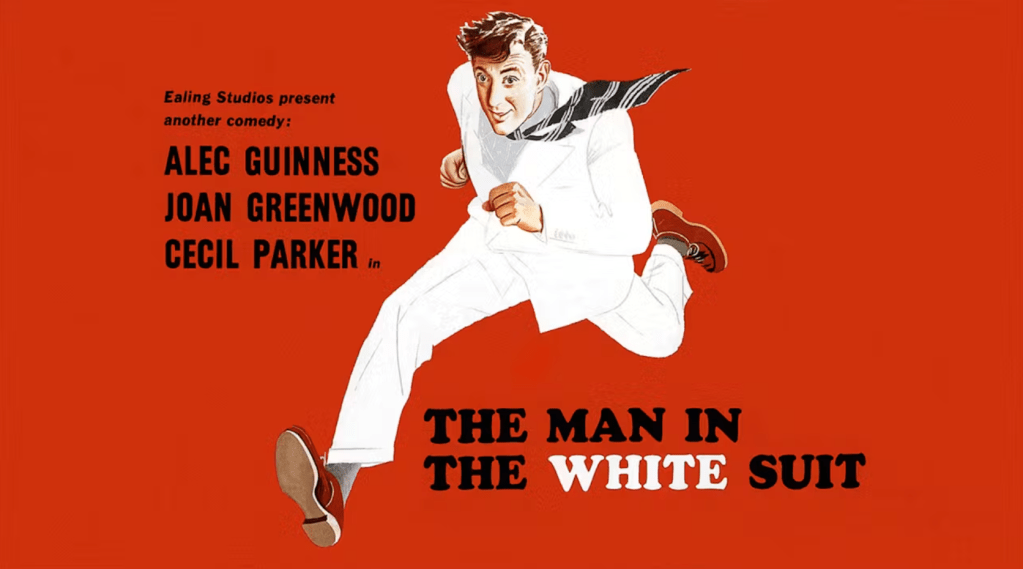

The films of Ealing Studios, especially their comedies, represent some of the very best of British cinema. Today the studio is most well known for its subversive, blacker than pitch comedies. The Ladykillers and Kind Hearts And Coronets are possibly the most celebrated films of the studio (and I’ve written elsewhere about Denis Price’s incredible performance in the latter) but The Man In The White Suit is one of their most quietly iconoclastic films, and represents Ealing at its most cynical. Directed by the legendary Alexander Mackendrick, it’s a cheerfully pessimistic, wry film about the heights of human invention, and the unforgiving nature of the capitalist world.

Alec Guinness gives his most energetic, youthfully exuberant performance since Herbert Pocket in Great Expectations as Sidney Stratton, a scientific prodigy who takes on menial jobs in textiles factories so he can continue his illicit experiments. What he finally produces is something that will rejuvenate the industry: a glowing white fabric that never wears out and never gets dirty.

Of course, this spells all sorts of problems that hadn’t even occurred to Stratton, but are all too plain to the workers who depend on the industry, and the owners who fear for their profits. The invention becomes a nightmare for all involved, culminating in one of Ealing’s most memorable set-pieces: a frantic chase sequence through cobbled streets, with businessmen and workers united in their determination to bury Stratton’s creation forever.

As with The Ladykillers and The Lavender Hill Mob, I have a personal connection with this film, having been introduced to Ealing as a child, and watching them with my grandparents. The moment when the mob mistakenly chases a baker clad in white, only for his daughter to hysterically shriek “Dad! Dad! What did you do??” has been lodged in my memory for most of my adult life. Watching as a child though, the films message clearly passed over my head, as my chief memories of the film were the excitement of the climactic chase and the memorable visual of Stratton glowing in his sublime white suit.

What struck me on revisiting the film is just how patient it is. The chase, dazzling as it is, only arrives near the end. Mackendrick spends much of the running time establishing characters, teasing out social tensions, and developing the central premise itself. The plot is almost incidental – the real drama lies in the contradictions of invention, industry, and self-interest.

Guinness gives one of his most humane performances playing a character who, on paper, really isn’t that sympathetic. Stratton is guileless, naïve, and utterly blind to the consequences of his work, so focused is he on his invention. He’s earnest and idealistic, but he fails to comprehend the implications of his work on the people he supposedly cares about, and it’s this thoughtlessness that makes him dangerous.

In many ways the premise is typical Ealing fare – as with Whisky Galore! and Passport to Pimlico, it portrays a community banding together against an external threat. The difference is that here the “enemy” isn’t an officious outsider or something as ephemeral as petty bureaucracy, but the positively cherubic Stratton. Mackendrick frames the ambiguity beautifully. Stratton might be “flotsam floating on the floodtide of profit“, but everyone else is so venal, and unpleasant to him, that it leaves the audience with a distinctly uneasy feeling. Mackendrick is resolute in his refusal to come down on either side of the argument though: is Stratton a hero, or are his pursuers justified? That unresolved tension is what makes the film so subversive, and so enduring. What is less ambiguous though, is the pessimistic view of progress. It’s shown as being a destructive force, damaging to industry and destabilising the status quo.

The only characters who we end up sympathising with are those who are entranced by Stratton, such as Joan Greenwood’s irrepressible Daphne, or those with more idealistic concerns, like Bertha (Vida Hope), the mill worker who quietly cares for him. Greenwood is probably best known today for her beautifully callous turn as Sibella in Kind Hearts And Coronets, but she’s brilliant here, playing a much more grounded character, someone who understands the way the industrialists think, but uses this against them, to support Sidney. The moment where he explains his process to her, sending her to the library to research his work for herself, is a really touching character beat, and marks her as more than the spoilt rich girl that she initially appears. The rest of the cast is populated with established British character actors, from Cecil Parker and Michael Gough to the skeletal Ernest Thesiger.

While at the time there was a clear allegorical feel to the film, linking Stratton’s suit to advances in nuclear technology, there’s a startlingly familiar, topical feeling to the film when watching today. You could easily draw a parallel between Stratton’s attitude and the rise of AI, an advance that promises untold benefits but also threatens industries, livelihoods, and social order. It’s also somewhat reminiscent of one of Guinness’ most celebrated roles in The Bridge On The River Kwai, in which he becomes so fixated on building a decent bridge that he becomes blinded as to which side he is on.

Visually, the film is more striking than most of Ealing’s output, thanks to Douglas Slocombe’s cinematography. Stratton’s luminous white suit, glowing unnaturally against the factories and streets, brings a science fiction element to the film, becoming a beacon of disruptive purity in a grimy world.

Mackendrick is one of my all-time favourite directors, and, to my mind, the greatest of the Ealing auteurs. He is cynical, but never cruel or mean-spirited; his endings are bittersweet, but there is always a glimmer of hope. Here, Stratton ends up ridiculed, defeated, and belittled, but Guinness gives him a flicker of inspiration as he wanders away – an irrepressible urge to begin again. As Stephen Frears puts it in one of the featurettes included with this release, Mackendrick embodied “everything that was iconoclastic, and disrespectful, and irreverent and full of energy and vitality” about Ealing. He was an outsider within the studio, making films brimming with originality and a recognisable, if uncharitable, view of British society. Perhaps he saw a little of himself in Stratton: an iconoclast whose work was dangerous, but original, exciting and irresistible.

The Ladykillers will always be my favourite Ealing comedy, but The Man In The White Suit is one of the finest films the studio ever produced – a subtle masterpiece that holds a very special place in my heart. It’s not as dark as The Ladykillers as meticulously crafted as Kind Hearts And Coronets, or as fun as The Lavender Hill Mob, but it’s the most quietly radical of the lot, a biting satire with a message that resonates more with each passing year.

Special Features

This collectors edition of the film comes with a 64-page booklet and A2 poster of orginal artwork; the extras include a newly filmed interview with Matthew Sweet on the film, as well as an extract from BEHP audio interview with Bernard Gribble, a commentary from film historian Dr. Dean Brandum and a featurette on the film.

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts