The question of remakes is one that will never end. Which ones are better than the originals? Which ones are worthwhile? But to me the more interesting question isn’t whether they surpass the films that inspired them, but whether they offer up anything new, or carve out their own identity.

By this measure, Sorcerer is a stripped down triumph. It’s probably William Friedkin’s third best film – which sounds like damning with faint praise until you remember he also made The Exorcist and The French Connection. The story had already been successfully adapted by Henri George Clouzot in his stark, noirish version. Friedkin’s film isn’t better or worse, but it’s different, and even better, it exists as it’s own thing.

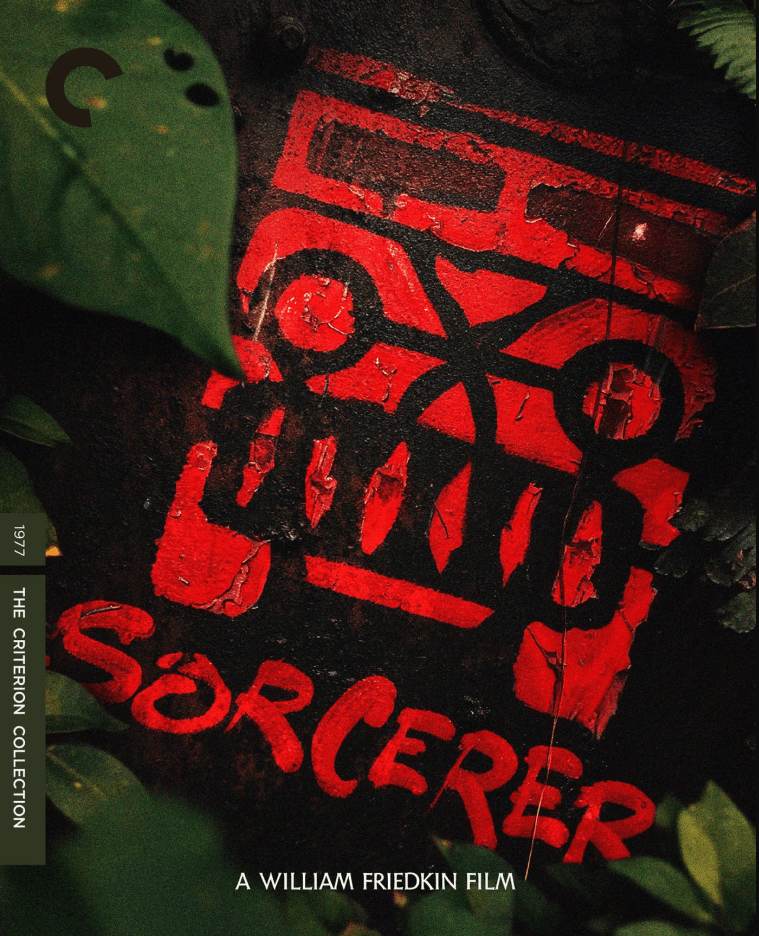

Today Sorcerer stands as one of the greatest remakes of all time, despite, or perhaps because of Friedkin’s insistence that it isn’t a remake at all. It’s a film that hits all the beats of it’s source material, (Georges Arnaud’s novel The Wages Of Fear) while retaining it’s own distinct personality and standing as something entirely unique. It’s unmistakably a Friedkin film, utterly infused with his distinct visual language, and an almost primal intensity.

The premise is perfect in it’s clarity and economy. In a rundown South American village, four fugitives are recruited for the life-threatening job of transporting highly unstable nitroglycerine across treacherous mountain roads to the main building site. The group – comprised of a hitman, a getaway driver, a terrorist and an embezzler – are all exiled from their native countries, and desperate to return to civilisation – desperate enough to take on a job that will almost certainly kill them.

Friedkin reportedly wanted Steve McQueen for the lead, but for me at least Roy Scheider is a much more believable choice. McQueen had the laconic-hero persona down pat, but I can’t quite imagine him bringing the requisite desperation and callousness to the part. Scheider’s lean, hungry look and his big, doleful eyes make him the perfect choice, despite Friedkin’s reservations. He begins as ruthlessly competitive with his fellow workers, (gleefully crowing over the extra shares he will get if the other truck doesn’t make it) but as the job begins to take it’s toll on the men, you can see that his heart’s not really in it – he cares about his fellow drivers despite himself, and it’s a trait that makes him both tragic and compelling.

The supporting cast is equally strong. McQueen’s star power might have brought Marcello Mastroianni and Lino Ventura aboard, which would have been something to see, but the actors Friedkin assembled instead bring a real sense of unpredictability to the film. Their relative anonymity makes it feel as though any of them could perish at any moment. Bruno Cremer gives the most humane performance as the exiled French businessman – clinging to his watch as the last vestige of his former “respectable” life. As the unsympathetic, close-lipped assassin, Francisco Rabal has potentially the hardest role, playing an outsider among outsiders, but succeeds in making him simultaneously enigmatic, ruthless and oddly magnetic. Amidou, playing the bomb-maker, was curiously the only cast member who was Friedkin’s first choice. He’s the least fleshed out of the four, but he still rounds out the group effectively. Together, the actors share an unsentimental dynamic – there’s a grudging respect that grows between them as the ordeal continues — and each actor makes the group’s exhaustion and grim determination palpable.

As well as Clouzot’s original film, the shadow of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre looms large over Sorcerer. Like Huston’s classic, this is a tale of men with nothing to lose, desperately clawing at that one last chance at fortune, only to find the sway of money is as destructive as it is alluring – as Friedkin himself described it, both films demonstrate “an underlying moral sense about what greed can do to otherwise decent people”. Even Scheider’s crumpled hat recalls the one Bogart wears. Yet where Huston focused on human greed, Friedkin is more concerned with existential dread and the indifference of nature.

Much of this sweaty, oppressive mood is due to Tangerine Dream’s moody, atmospheric score. Unusually, the band composed the music before shooting began, and the result is a soundscape that feels both pulpy and ethereal – it’s almost primordial, recalling the hypnotic scores of Werner Herzog films, and blurs the line between reality and hallucination.

And then there’s that famous bridge sequence. Shot in a storm, with rotting planks, thrashing cables, and trucks swaying over a raging river, it remains one of the most harrowing, tense set pieces ever committed to film. The first truck going across it is suspenseful enough, as pieces of the bridge splinter and break, but then the second rolls up. It’s almost unbearably suspenseful scene, with every groan of wood and rush of water feeling like a countdown to disaster. Friedkin deploys every cinematic technique he knows, and the result is exhilarating. It’s cinema as pure tension, a sequence that seems to stretch time itself.

The film’s failure at the box office is well documented – coming out the same year as Star Wars, and featuring a title that conjured up fantasy imagery did the film no favours, and it quickly vanished from screens. But it’s had a severe reappraisal in recent year, with champions like Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan and Francis Ford Coppola singing it’s praises. Aside from a few quibbles, (The four introductory scenes are a bit messy, and I’m not a huge fan of the extended hallucinatory scene towards the end) Sorcerer hasn’t aged a day, and I would put this largely down to the pared back storytelling – predominantly relying on visual storytelling rather than dialogue – and the jungle environment, which helps it feel timeless compared to the more contemporary settings of the time.

Ultimately, Friedkin was right – Sorcerer is much much more than a remake. To him, it was a film about “the mystery of fate… purgatory and redemption.” And that’s what makes Sorcerer endure today, more than the spectacle and characterisation – it’s the dreadful inevitability that seeps into every frame. It remains one of the leanest, most gripping, and most nerve-shredding films ever made.

Special Features

The main improvement here is the colour grading, which is a huge step up from the previous EOne release, which was so garishly over-saturated that it almost felt like a cartoon. This new restoration has a much more natural feel, more in-keeping with the film’s grounded realism – the director approved audio remaster is also a massive improvement.

Alongside the usual selection of standard extras, this release includes Friedkin Uncut, a documentary on the director featuring interviews with Wes Anderson, Francis Ford Coppola and the man himself, as well as a newly filmed conversation between director James Gray and critic Sean Fennessey on the film’s legacy, and perhaps the biggest draw: the notorious interview between Friedkin and Drive director Nicolas Winding Refn. It’s a playful, spiky conversation where Friedkin sets the tone immediately – when Refn calls him Billy, he replies “you can call me Mr Friedkin.”

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Post your thoughts