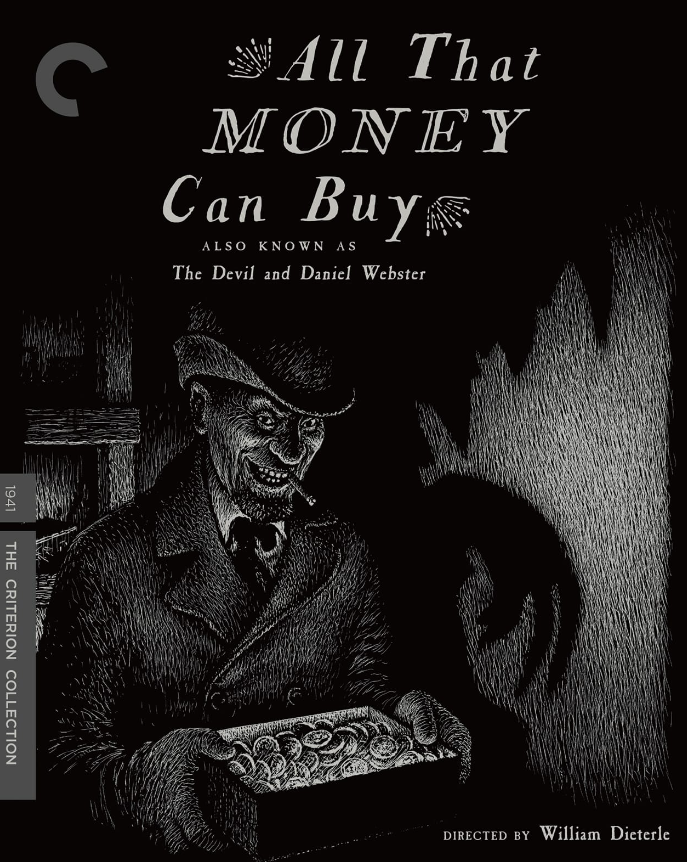

All That Money Can Buy, also known as The Devil and Daniel Webster, also known as Daniel And The Devil, also known as Here Was A Man, has had an especially fraught history. This release from Criterion restores crucial character moments as well as some innovative editing techniques. It marks the first time the 106 minute version has been available for over 50 years, and the first time ever that it has been seen in the form and quality intended by the filmmakers.

The Faustian short story by Stephen Vincent Benét is so ubiquitous that it’s been referenced in media as disparate as The Simpsons and Inside No.9. It’s the story of Jabez Stone (James Craig) a hard-working farmer fallen on hard times, who absent-mindedly offers to sell his soul for two cents. Well, speak of the Devil and the Devil shall appear, here in the form of the jovial Mr Scratch (Walter Huston) who grants Jabez seven years of prosperity in return for his soul. When the time is up, and Scratch comes to collect, Jabez pleads with the real life senator and presidential candidate Daniel Webster (Edward Arnold) to represent him in a trial against the Devil.

Like a macabre inverse of A Matter Of Life And Death, where a celestial court decides the fate of a man, here Jabez’s fate is determined by a jury of the damned – a rogues gallery of American ne’er-do-wells. Unlike the very British nature of the Powell and Pressburger film though, this is a distinctly American film. Webster refers continually to the pioneering nature of Jabez, and the message at the end seems to be that yes, Benedict Arnold may have been a villain, but at least he was American! As Webster puts it in his summary: “Don’t let this country go to the Devil!“

All That Money Can Buy occupies a strange place in film history, beginning production at RKO alongside Citizen Kane, and yet largely forgotten today. What’s most interesting about this film is the way it feels like a combination of old fashioned and modern film-making techniques. The use of editing, trick photography and low-key lighting recalls the silent cinema of German Expressionism, while the long uninterrupted dialogue scenes, the impressive depth of field, and the deep focus gives it a much more contemporary feel.

James Craig is fine, if a bit broad, and successfully depicts Jabez’s basic decency combined with the frustation that makes him an ideal target for Mr Scratch. However it’s quite a thankless role; he has to be credulous as hell at the start and then increasingly unsympathetic as he falls under the sway of the Devil, and none of this is depicted particularly subtly (His repeated utterance of “Consarn it” wears thin very quickly).

Edward Arnold is more successful as the titular Daniel Webster. Arnold effortlessly brings a real sense of gravitas to the role but the character himself, a seeming paragon of virtue, is a very old-fashioned archetype, and one that feels beholden to the legend of his real-life counterpart.

One performance that hasn’t aged is Walter Huston as Mr Scratch. He clearly relishes the opportunity to play such a malevolent character, and his ever-present toothy grin makes him one of the most memorable depictions of the Devil (and it remains the only one to be nominated for an Oscar). His introduction scene is one of the most effective entrances in cinema history, emerging from a blinding light in a barn, sending the farm animals into a frenzy.

Director William Dieterle casts the supporting roles cannily, using reliable character actors like Jane Darwell, Jeff Corey, Gene Lockhart and John Qualen. Qualen in particular is perfect casting, his rat-like features and nervy manner a perfect fit for the stingy Miser Stevens. He imbues the money lender with a surprising amount of pathos for what could have been a fairly one dimensional character. His quiet, mournful delivery of “Aren’t you afraid?” in his final scene is simply chilling, and his fate inevitably raises the stakes.

Simone Simon’s temptress is another element that works really well, almost a precursor to the femme fatale. Her performance here is rumoured to be the one that landed her most iconic role, in Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People, where she plays a similarly predatory character.

As with The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Dieterle makes effective use of modern film techniques and special effects, but deploys them with an admirable amount of restraint, to often disarming effect. The calling card that ignites in Scratch’s hand is a great example of this. These are fantastic effects but depicted in an almost throwaway fashion, which oddly serves to make them even more memorable.

The film is rarely genuinely scary, instead taking a more wry approach to its subject. There are some incredibly eerie sequences though, such as the party Jabez throws, with the haunted gathering peering through the window, and the imagery used to depict someone’s soul leaving their body. The fateful dance with Miser Stevens is similarly chilling, and brings to mind later horror classics like Dead Of Night and Carnival Of Souls. Similarly, the malignant , all-too brief negative images of Scratch that have been restored in this new version suggest a disturbing omniscience to the character, that adds an incredibly sinister dimension to the character, and feels like a direct influence on the unnerving inserts from The Exorcist.

Bernard Hermann’s score is highly evocative, albeit in an unobtrusive way. He always maintained his job as composer was to “get inside the film” and he manages this here and then some – using the score to accompany the action, sometimes literally. The Miser’s Waltz is a particularly great example of this, punctuating the rhythms of Webster’s speech while also accompanying Stevens’ fateful dance with the Devil.

This being a Criterion release, it almost seems redundant to point this out, but the restoration – from a 35mm source – is stunning. The inky black shadows and blistering brightness from the numerous flames are rendered beautifully, while the benefit of the stylised staging and shot composition means that visually, the film hasn’t aged all that much.

This is the contradiction inherent in All That Money Can Buy that makes it a fascinating watch today. It’s an old-fashioned parable with a moral that is timeless. The film itself features some mannered, folksy performances that feel like a product of their time, but elsewhere it’s a work of remarkable subtlety and a decidedly singular artefact of old Hollywood, and a macabre delight. Well worth a watch.

Special Features

Extras include an audio commentary from film historian Bruce Eder and Steven C. Smith, biographer of composer Bernard Herrmann; a comparison between the different released versions of the film; A reading of the original short story by Alec Baldwin; Radio adaptations of Benét’s short stories The Devil and Daniel Webster and Daniel Webster and the Sea Serpent.

![The Cat And The Canary Blu-ray review: Dir. Paul Leni [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/image-5.png?w=1024)

![Crimson Peak Limited Edition 4K UHD review: Dir. Guillermo del Toro [Arrow Video]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/crimson-peak-4k-arrow-video-highdef-digest-full.jpg?w=1024)

Post your thoughts