You often hear older films described with the phrase “it wouldn’t get made today…,” this is usually reserved for some reactionary point of view that yes, the film is probably quite rightly left in the past. The Fisher King is different, a whimsical story that on paper seems perfect fodder for 21st century moviegoers.

It’s an allegorical knight’s tale about shock jock Jack Lucas (Jeff Bridges), who seeks redemption by playing matchmaker for a homeless eccentric, Parry (Robin Williams) with a tragic backstory, and a fixation on the Holy Grail. On paper, it sounds quirky and heartwarming. But with Terry Gilliam at the helm, it’s anything but predictable. Gilliam’s refusal to make his characters easily lovable ensures that The Fisher King is more challenging and rewarding than your typical redemption story.

As Gilliam himself puts it on the commentary for this release:

“I hate films that are begging the audience to love these characters, to open their hearts to these people as if the audience are that much better off… We’re all in the same situation, frankly.”

This sentiment shapes the characterisation in The Fisher King . We’re so used to the polished perfection of characters in modern Hollywood that the more unattractive traits of the four main characters here is jarring, but incredibly refreshing. Jack’s transformation from self-absorbed jerk to something resembling a good person is especially well-handled. Bridges plays the role broad and obnoxious, leaning into Jack’s self-serving nature. His redemption doesn’t come at the point where we might expect it to, and clearly not when *he* thinks it does. He doesn’t help Parry out of selflessness but simply to ease his own guilt, just reinforcing his own narcissism. Only at the film’s climax, when Jack finally chooses to help Parry for Parry’s own sake, does he truly begin to change. It’s one of the rare cases where a heel-turn like this feels truly earned.

Bridges gives a loud, often quite broad performance, but one that is free of vanity. He weaponizes the easy charm that usually makes him so likeable, to underscore Jack’s selfishness. His dynamic with Robin Williams is fascinating. It’s not so much that they have great chemistry, but their contrasting performance styles compliment each other perfectly. It’s as if Williams brought out the more exuberant side of Bridges, and Bridges in turn draws a more disciplined performance from Williams. It’s not a typical zany Williams performance by any means, despite the more comic moments. He reins it in and delivers a raw, poignant portrayal of trauma that never veers into schmaltz. His exuberant outward persona is tempered by an undercurrent of vulnerability, and it’s quite possibly the best film performance of his career – the moment where he quietly sings Lydia The Tattooed Lady in the Chinese restaurant is beautifully observed, and he nails his more traumatic scenes, giving an all-too believable depiction of mental anguish that is difficult to watch.

While the two male leads drive the story forward, the rest of the ensemble add crucial emotional depth and perspective to the narrative. Mercedes Ruehl is especially memorable as Anne, Jack’s long-suffering girlfriend. The only truly likable character in the film, Anne is tough, abrasive, and deeply smitten with Jack despite his flaws. Ruehl perfectly balances these contradictions, and her Oscar win for Best Supporting Actress feels entirely deserved. In contrast, Amanda Plummer’s Lydia, Parry’s love interest, is a subversion of what we would now call a Manic Pixie Dream Girl. She’s an unapologetically eccentric character – picky, clumsy, and argumentative, yet still endearing in her own way. The romance between Lydia and Parry, while unconventional, is undeniably sweet, and provides the film with its much needed heart.

Gilliam populates his world with memorable faces in supporting roles too, with David Hyde Pierce, Kathy Najimy and Tom Waits popping up in cameos, while Michael Jeter briefly steals the film as a homeless cabaret singer. Jeter reportedly ad-libbed a chunk of his dialogue, and the interplay between him and Williams is so full of energy you wish they had more scenes together. His performance is equal parts comic and tragic – from his incredible rendition of Everything’s Coming Up Roses to his and his final poignant scene with Bridges is full of pathos – he makes an indelible impression with minimal screentime.

The Fisher King marked several firsts for Gilliam: his first present-day setting, his first script not written by himself, and his first attempt at grounding his story at least partly in a realistic setting. Yet it retains hallmarks of his previous work; All Gilliam’s films to this point were preoccupied with vivid imaginations, be it a child’s mind (Time Bandits), the fantasist older mind (Baron Munchausen) or a daydream world of escapism (Brazil). However where in Brazil, the daydreaming of Sam Lowry is a way for him to escape the monotony of his dreary office life, in The Fisher King, Parry’s visions, particularly the terrifying Red Knight, are a psychological coping mechanism for his grief. The Red Knight’s presence in the contemporary setting is both surreal and haunting, and the climactic confrontation between Parry and the knight is visually striking and deeply unsettling.

While The Fisher King is often unsubtle—its allegories are on the nose, and Bridges and Williams play their parts broadly—it’s the quieter moments that linger. Parry’s fractured personality is subtly conveyed through visual cues, such as his reflection divided by beveled glass or his flapping sleeves transforming into a straitjacket. The screenplay by Richard LaGravenese is an actor’s dream, giving depth to the four main characters while also dropping wonderful aphorisms (“you’re the best thing since spice racks”) left right and centre.

The film does also boast one of cinemas most perfectly conceived and executed set-pieces in the Grand Central ballroom sequence. As Jack and Parry follow Lydia through the station, the sea of rushing commuters gradually transforms into a ballroom, offering the audience a brief glimpse of the beauty in Parry’s view of the world. It’s one of the most iconic moments of Gilliam’s career – a perfect blend of surrealism and a very relatable feeling of longing, capturing Parry’s romantic idealism as only Gilliam could.

I don’t know if this is praise or criticism, but the most impressive direction in the film comes when the showy visuals end, and Gilliam just allows his actors to act. In the big break-up scene between Ruehl and Bridges, he does some brilliantly un-showy direction, moving the camera between the two without ever drawing attention to itself. All the traits that usually make Bridges so likeable here serve to make him pretty detestable, while Ruehl’s understated shock is devastating. Gilliam has said that it’s the scene he’s most proud of and it’s hard to disagree.

The Fisher King isn’t perfect, but its imperfections are part of its charm. It’s a messy, poignant exploration of redemption, grief, and human connection. While its broad strokes may not suit everyone, its heartfelt core, powerful imagery and moments of brilliance make it unforgettable. Critics often maintain that only Gilliam could have made The Fisher King. Really though, the bits that resonate best today are the un-Gilliam moments – the tonal subtleties and character driven scenes that show the director trying something new and vital.

For me, I think if this had a different, less eccentric director at the helm I might like it more. But then if anyone else directed it we would have been denied moments of inspired imagination like the Grand Central Ballroom sequence, that nobody else could replicate. So no it might not be perfect, but I wouldn’t change a single scene.

Special Features

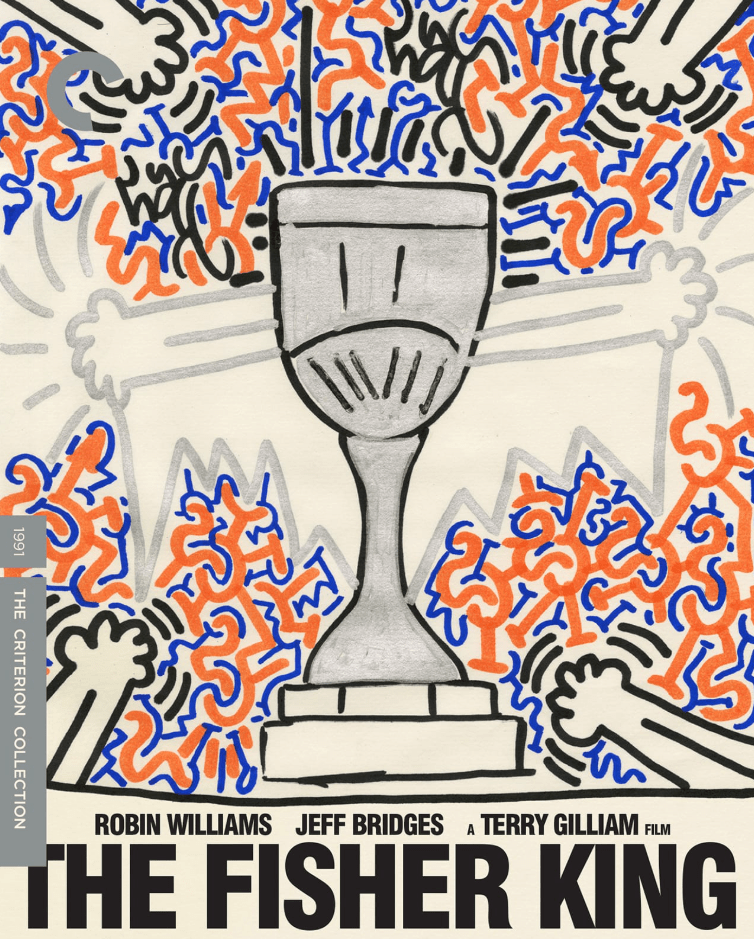

Extras include an audio commentary from Terry Gilliam, Interviews with Gilliam, producer Lynda Obst, screenwriter Richard LaGravenese, and actors Jeff Bridges, Robin Williams Amanda Plummer, and Mercedes Ruehl, Interviews with Keith Greco and Vincent Jefferds on the creation of the film’s Red Knight and more.

The Fisher King is out now from the Criterion Collection

Order yours: https://amzn.dp/B0DHLLDMSH

![Unquiet Guests review – Edited by Dan Coxon [Dead Ink Books]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/ug-reddit-ad-e1761690427755.jpg?w=895)

![Martyrs 4K UHD review: Dir. Pascal Laugier [Masters Of Cinema]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/image-1-e1761586395456.png?w=895)

![Why I Love… Steve Martin’s Roxanne [1987]](https://criticalpopcorn.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/roxanne.jpg?w=460)

Leave a reply to steveforthedeaf Cancel reply